12. Partnership

CARE believes that it is only through the collective efforts of many actors that overcoming poverty and injustice, and saving lives during emergencies, can be achieved. CARE has long promoted working with local institutions in development settings, to support local capacity, ownership and sustainability. Similarly, CARE increasingly works with partners when responding to emergencies, recognizing that this not only saves lives and achieves greater reach and scale, but also leads to sustainability.

1.1 CARE’ s Strategic Commitments for partnering in emergencies

1.2 Partnership is…

1.3 What do the guidelines cover?

1.4 Who is in charge of the ‘partnership’ function?

1.4.1. Roles and Responsibilities for partnerships (outside of emergencies)

1.4.2 Partnership management functions in an emergency response team

It is not always possible to establish partnerships before an emergency hits. Often, this is done ‘on-the-go’ which results in a tendency to ‘subgrant’ rather than partner more meaningfully. While this should be avoided, it is never too late to partner, however. Even in the midst of crisis, responding in partnership can add substantial value and should always be explored, while being mindful of the challenges and pitfalls. The guidelines are relevant for such situations and do not presuppose previous experience of partnering. Nor do they assume that all offices have partnering procedures or existing partners.

This being said, the best time to establish partnerships is outside of crises. Partnering is complex and requires time, effort, courage and vision. Getting to know another agency (its objectives, capacities, and culture), building trust, defining the added value of the partnership, and agreeing on a joint programme, can best be done over time, as part of the Emergency Preparedness Process. See Annex xx: Partnering as part of the EPP process (Guidelines currently under revision).

Preparing together, before an emergency hits, leads to:

- More predictability of the joint response (what we aim to achieve together, who will provide what and play which role based on our respective assets and complementarities, how we will conduct joint needs assessments, what will trigger a response,)

- Readiness to kick off or scale up the partnership (partnership agreement existing or pre-agreed, capacity and due diligence assessments completed, risks assessed and mitigated, procedures pre-agreed for fund transfer and programmatic/financial monitoring, pre-agreed and tested tools for response, from pre-costed project proposals to monitoring tools)

- Greater readiness of the partner’s organization to respond (key gaps pre-identified and capacity development underway, readiness to scale up, e.g. staff; funding, procuring supplies, managing heighted security) CARE’s enhanced readiness to respond in partnership (updated mapping of local capacities and partners, trust established with identified partners, procedures in place, staff ready and skilled to support partners, simplified compliance and monitoring tools; pre-agreed joint communications and media protocol).

Some simple preparedness measures for partnering might include:

- identifying existing or new partners to include in preparedness planning-for example, it might be possible to identify partners in disaster-prone areas

- keeping up-to-date mappings of local organisations and their capacities

- Creating space for discussions with and feedback from local organizations on how to build mutually valuable and effective partnerships

- offering training on emergency approaches and standards to partners (including Sphere, gender, humanitarian accountability)

- building the capacity of staff as trainers

- documenting and translating standard programme approaches and tools

- concluding framework agreements that cover collaboration in emergencies

- establishing partnership agreement and funding procedures and tailoring them for emergencies

- providing training for support and programme staff on roles, responsibilities and good practices to manage partner relationships

- including provisions on emergency in normal sub-grant/partnership agreements.

The principles of partnership outlined in Section 1 have gradually been incorporated into working methods and are increasingly seen as part of a ‘new business model’ for CARE in emergencies, wherein local partners and local communities are not only at the heart of the response, but are also involved in prevention and preparedness right through to early recovery and longer-term development.

The following sections will assist in considering whether and how to work with partners, critical success factors of partnerships, and which steps to take in each phase of the partnership process.

3.1 Why do it?

3.1.1 Issues to consider for deciding partnerships

3.2 Good reasons to partner

3.3 Partnering for the wrong reasons

3.4 Who decides?

Recent survey feedback from CARE’s experiences working with partners reveals rich lessons learned, the most common of which are listed here as critical success factors.

| DO: | |

| Ensure the value addition for both parties is clear | A clear decision-making process on whether and who to partner with will examine and clarify what value the partnership brings to both parties. |

| Set clear roles and responsibilities | Be clear on the division of labor-which functions will be handled by CARE, which by partners, and what TA will be provided. Define this in contracts and project documents. |

| Delegate power | Sharing power is often a challenge for CARE. While it might be necessary to support or handle some activities, partners also need room to work without being micro-managed. |

| Involve partners in all phases of the project cycle | While not always possible, partners should ideally be jointly involved in the response strategy, needs assessments, program design and proposal development to avoid misunderstanding and increase ownership. |

| Consult and be transparent | Decision-making should be as transparent as possible between CARE and partners, including on budget and finances. It is also important to share information and seek input on decisions-but without over-consulting. |

| Budget adequately | Overhead and staffing costs are very real issues for CARE and this can hinder a fair partnership agreement. While partners are doing the bulk of the implementation, CARE often does not allow partners to adequately cover their operational costs. Investing in the partners staffing structure and overhead is a critical success factor for any response and key for a successful partnership. |

| Have good internal coordination | Confusion on roles and authorities can lead to too many people getting involved in internal decisions and procedures, causing delays and mixed messages. Be clear who must be consulted and who signs off on what. Use a management model where a field-based team coordinates routine matters and a senior management team meets to resolve policies and issues. |

| Get the field team right

|

One field-based programme staff member should be the focal point for all dealings with a partner. Support and finance staff should also be placed in the field for assistance with the work. Try to use local staff with technical ability, good attitudes, and communication and negotiation skills. Ensure that they are mandated to take decisions, as well as to consult and inform senior managers. |

| Act as equals | Local agencies often complain of being treated as servants by INGOs. While its resources and role as steward of donor funds do place CARE in a powerful position, attitude also matters. It can be too easy for staff to think, ‘We know better’ or ‘We can do better’. Even if CARE has expertise, partners also add value. |

| Accept and manage risk and imperfection | Partnerships can be marred by risk aversion and perfectionism. Intense questioning of details can delay contracts, disbursement, programme design and implementation. A particular issue can be marred if support staff feels their main role is to protect CARE from partner mistakes. Staff should be encouraged to manage rather than just to strive to avoid these issues. |

| Learn from partners | Partners have rich knowledge and expertise about the operational context we are working in, that CARE does not always tap into. CARE should engage in strategic and programmatic discussions with partners, discuss developments and scenarios of the context, and engage in joint preparedness as well as strategic planning processes. There is a lot more we can learn from our partners that can enhance the quality and effectiveness of our response. |

| Prepare and nurture partnerships outside of emergencies | Pre-emergency is the prime time to invest in partnership. It is difficult to establish trust and build relationships during the height of an emergency when the focus must be on saving lives and alleviating suffering. Ideally, CARE will develop partnership relationships during times of non-emergency. Long term investments in capacity building will enhance the quality and effectiveness of response. It is important to have access to committed and consistent funding for capacity development for partners (or for CARE from partners!) in topics including security management, financial management, humanitarian standards, emergency preparedness and gender in emergencies. |

| Make sure support systems are responsive to partnership | Current procedures are heavy on paperwork and reporting and not conducive to rapid emergency work; even less so when engaging and working with partners. Simplify procedures where necessary and keep things light for our partners where possible. But make sure to meet donors and auditors requirements. |

| Invest in building interpersonal relationships | People need to trust and respect each other if they want to establish a fruitful relationship. The representatives of organisations are individuals, and therefore interpersonal relationships are central to a successful partnership between organisations. |

| Accept and manage different roles and tasks | Working in partnership requires a different skill set amongst CARE staff. Moving away from that of direct implementer, the role for CARE staff will focus more on building relationships, monitoring, capacity building and contract management. |

DON’T: |

|

| Create inflated expectations | Discuss expectations with partners from the start. It can be dangerous if a partner sees simple sub-grant as something more than it is, or if promises to build capacity are not delivered. But it is good to have realistic visions for relationships, as they provide something to work toward. |

| Delay on payments and deliverables | Ensure that the Country Office’s financial and administrative systems are flexible enough to allow for real time transaction of funds, resources and other support as required by the partner, in order to set them up for success. |

| Overfund or overstretch the partner | It is important to have a clear sense of other projects and overall capacity of the partner to carry out the agreed upon work. Good partners are likely working with other NGOs and an effective balance needs to be maintained. |

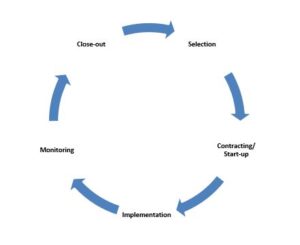

Working in partnerships could be divided into 5 different phases. These phases are coinciding with the moment in the project cycle. The figure below represents the phases in the partnership process for a single project during a rapid onset emergency. In reality however, you may have strategic partners for a longer period beyond the duration of a project.

Ideally, the partnership process is started as part of your preparedness planning. This basically means that the selection process has been completed during “peace” time, resulting in a framework agreement to work with a partner during an emergency. This will save considerable time once an emergency hits. Moreover, identifying partners during your emergency preparedness planning will provide an opportunity to invest in capacity development of the partner. Partners are usually selected before proposal design, but this is not always possible.

Each phase in the process has some critical steps that have to be taken. The exact steps in the partnership process may vary in each response. The reality of an emergency is often complex, hence the below guidelines should be tailored to your specific needs and context. It is recommended however to adhere as much as possible to the specific steps outlined below.